“The first time I tasted Thai food I hated

it,” says Australian master-chef David Thompson. “It was the early 1980s in a

little restaurant in Bondai [

“The fish cakes were as rubbery as Hell; and I remember hating a spice called lemongrass. It’s ironic how life turns out.”

Indeed it is. Despite the inauspicious introduction to Thai fare,

Thompson currently holds the only Michelin star ever afforded a Thai restaurant

– Nahm, located in London’s West End. His first cookbook, Thai Food, a voluminous 15-year labour

of love, won practically every culinary book award going. And, extraordinarily, he was invited to advise the

That’s an emphatic about-face – so what exactly

changed his mind? “Just living in

During his stay he met elderly “Khun Yai” Sombat Janphetchara, heir to a royal tradition of culinary refinement. She walked Thompson through the fundamentals of Thai cooking, guiding his first shaky steps on a journey towards a chorus of fawning accolades:

“David Thompson produces dishes more

sagacious, undulating, bewitching and boisterous than any you will find even in

The man himself, with typical Antipodeans’ modesty, is dismissive of the plaudits, telling New Arrivals he won his Michelin star after “I slept with the reviewer!

“I always ignore that stuff. I go and eat in

the streets and markets of

Thompson’s example illustrates the internationalization of Thai food, though this is a relatively recent phenomenon. 25 years ago the average Western taxi driver could’ve no more located a plate of passable Pad Thai than the final resting place of the Holy Grail, but things have come a long way in two decades.

Thai cuisine captured foreign appetites with

such gusto that the fare now forms a staple on those infallible barometers of

popular taste – pub menus – across continents. Chef Khamtane Signavong, author

of Lemongrass and

Sweet Basil, and

owner of an overseas franchise, reckons the Thai grub in

The rapacious hunger for this edible export

currently feeds 9,183 overseas outlets; a figure expected to mushroom by some

3,000 in 2006 with the opening of new restaurants in Africa, the Middle East

and other parts of

All this amounts to a rather tasty cash cow,

with orders from abroad boosting agricultural exports around 100 billion baht a

year on average, according to Yuthasak Supasorn of the National Food Institute.

Aggressive public relations campaigns begin to explain why culinary thrill-seekers in the farthest-flung corners of the globe are emitting whoops of delight into their bowls of tom yum.

Another reason is greater economic affluence facilitating more travel. Increasing numbers of Thais emigrate, lured by promises of decent salaries in the West, where being a chef is not considered subservient. And as more tourists visit the kingdom, most sample the local chow.

While here, they’re also faced with a

plethora of cookery courses. One of the finest is the luxuriant

“And once prepared, cooking time is very fast – just two or three minutes. So they can easily get to grips with the cooking part.”

The fresh produce favoured by Thai cooking – featuring beneficial doses of medicinal herbs and spices – also popularises the cuisine immeasurably, as people everywhere become increasingly health conscious.

“You have to look at the Asian diet and European diet,” Khun Khamtane tells New Arrivals. Europeans eat dairy-heavy dishes packing excessive cholesterol. Thais eat lightly – filling up on water-based, calorie-low rice – but often. They snack constantly, thereby moderating blood sugar levels while swerving the peaks and troughs that cause binge-eating.

Pitak expounds on the magical properties proffered by stock Thai ingredients: “Ginger and galangal are good for gastroenteritis and skincare; lemongrass is good for the urinary tract and back pain; and chilli has vitamin C comparable with two oranges – and it's good for headaches.”

Of course, healthy or not, generalising about Thai food as a single, cohesive entity does considerable disservice to the provincial diversity. As Thompson discovered on his travels researching a forthcoming book on street food, “the regional difference is just vast.”

Often Thai cookbooks divide their chapters

by region – as is the case with the recently released

Thai Way of Life: The Dusit Cookbook, which files recipes for som tum and sticky rice in the “North & Northeast” section.

Thai cuisines evolved by absorbing varied Eastern influences – Szechwan Chinese, tropical Malaysian, the creamy coconut sauces of southern India and aromatic spices of Arabia. Somehow they’re all seamlessly blended into the national cuisine, says Thompson:

“They’ve [Thais] had the capacity to absorb foreign influences, digest them then express them in a particularly Siamese way. It’s always been their peculiar genius.”

But how are foreign practitioners to appropriate a cuisine alien to their native tongues? David Thompson says it requires a major overhaul of foreign taste profiles to adapt: “You need to discard the preconceptions that Western food creates; the idea of taste.

“Some [Thai] techniques are radically different: as a cook you look at them saying ‘This can’t work’; and as a consumer you shake your head in disbelief that it’s so delicious. Thai food abounds with such paradoxes.”

A fundamental contrast between Thai and Western exists in the complex seasoning. Meals should deftly juxtapose sweet, sour, salty and hot flavours, called in Thai “rot chart” (clear, balanced taste). This applies to individual dishes as well as the overall meal. The brew of “chilli-hot” spices heightens diners’ appreciation of flavour, by sensitising – read: scorching – the palate.

“Cooking Western is like playing drafts,

whereas cooking Thai is like playing chess,” notes Thompson.

“Cooking Western is like playing drafts,

whereas cooking Thai is like playing chess,” notes Thompson.

Food is inseparable from a culture whose original greeting was “gin khow reu yang?” [Have you eaten yet?]. Word-of-mouth wisdom passes down generations via instinctive, sensual collaboration, rather than by following written instructions.

Neither Khamtam nor Pitak trained formally, yet one authored a cookbook; the other teaches cooking at a top-end resort.

Historically, chefs abroad had to make do with

taste-compromising dried or powdered herbs and spices. “I don't know how long

they took to transfer ingredients,” says Pitak, of his years in the middle-east,

Thompson and Khamtam claim importing produce or using local substitutes these days presents no obstacle to freshness or authenticity.

Globalization, by definition, blends cultures and traditions. With Thai food it engendered a trend for “fusion”: creative, experimental and “more interesting” to those like chef Pitak; an inauthentic travesty to others like Thompson, who says “you end up with an unholy united nations on a plate.”

But such is the way of the world; things

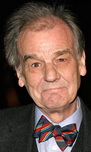

will only get even more muddled. Now the much-loved, legendarily-soused British

chef Keith Floyd, the eccentric behind decades of television series and 26

best-selling books (soon to be 27 with Floyd’s

Thailand), has set up a Thailand-based restaurant franchise, featuring a

cooking school, in cahoots with the Burasari Resort Group.

“I must be one of the few who has dared to show Thai people how Thai food can be presented,” he recently declared. Cheers, Keith!

But Khamtane Signavong believes nationality is no barrier to brilliant Thai food: “Asians cook farang food all the time. If you want to dig deep into a cuisine you have to learn more, and David Thompson did that in a very nice way.

“We respect him dearly, because he has taken

Thai food to a different level. He’s a man with vision.”

-- Published by New Arrivals, 2005